Free Will

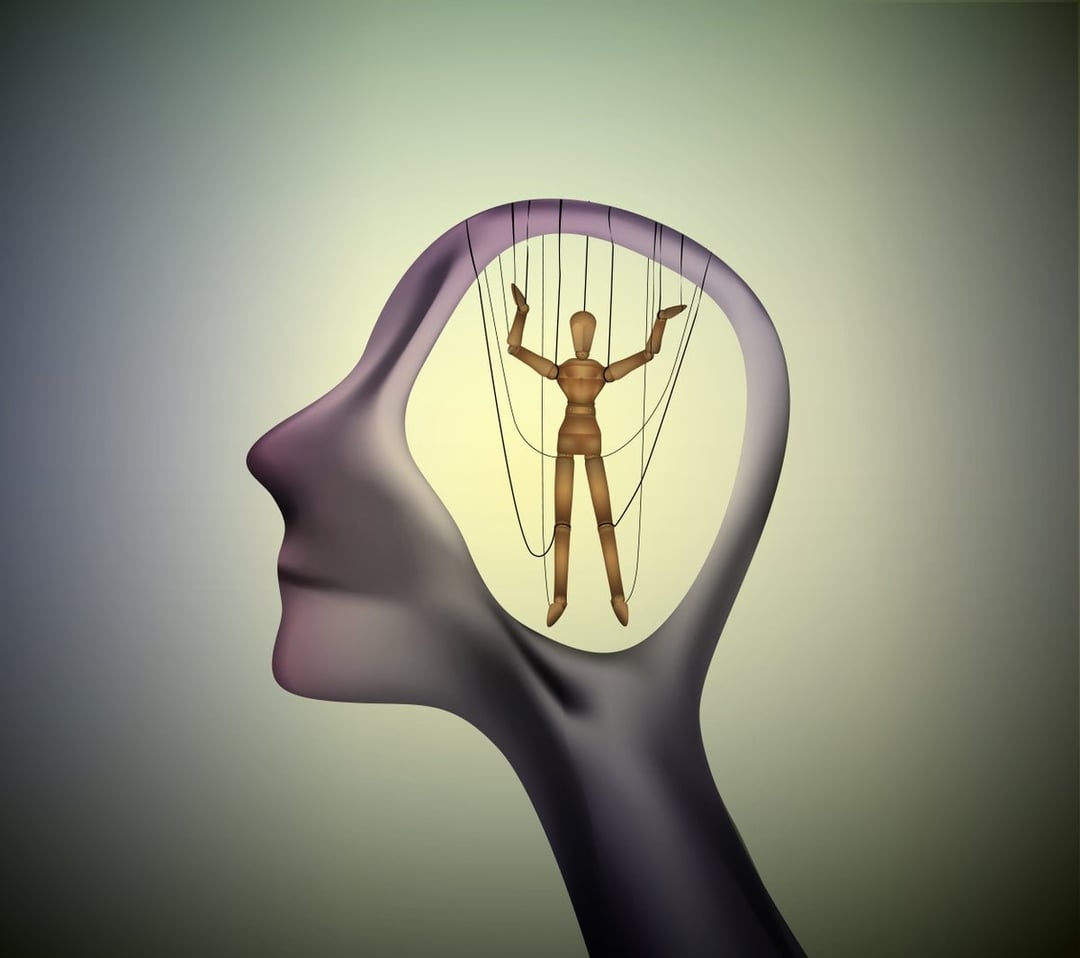

In a world increasingly defined by scientific discovery and technological advancement, the question of free will in a deterministic universe remains one of the most enduring and profound puzzles. Are we the architects of our destinies, or are our choices mere illusions shaped by forces beyond our control? This debate is not confined to ivory towers but resonates deeply with our understanding of morality, responsibility, and the human condition. At its core lies a basic tension: if the universe operates according to deterministic laws of physics, is there any room for genuine choice? The implications of this inquiry stretch from the personal realm to societal structures, influencing how we judge ourselves and others.

Determinism, as a concept, posits that all events are predetermined by prior states of affairs. This is the view from classical mechanics, epitomized by Isaac Newton, that the universe is a huge, clockwork machine. Every event and action is the inevitable result of a preceding cause. From this perspective, the path of every particle—and, by extension, every human thought and action—is theoretically predictable given enough information. This deterministic framework found further endorsement with the advent of neuroscience, where studies have shown that our brain activity often precedes our conscious awareness of making a decision. If the brain, like any physical system, obeys deterministic laws, can our choices really be free?

Philosophers have grappled with this dilemma for centuries, offering divergent perspectives. Hard determinists hold that free will is an illusion, and that if our actions are the inevitable result of antecedent causes, moral responsibility is merely a convention of society rather than a metaphysical fact. Compatibilists, on the other hand, think that free will and determinism are not mutually exclusive. They argue that freedom lies in our acting in accordance with our desires and intentions, even if those desires themselves are determined. At the other extreme, libertarians-philosophical libertarians-advance the reality of genuine free will, frequently appealing to metaphysical or quantum considerations in an attempt to get themselves out of the deterministic bind. Quantum mechanics, with its probabilistic nature, has been called upon as a possible escape hatch, but randomness itself doesn’t appear to supply a sound basis for the sort of meaningful choice that could undergird genuine free will.

To make this rather abstract debate a bit more concrete, consider a real-world scenario in which someone commits a crime. According to a strict determinist perspective, their behavior was bound to happen, given the genetic predispositions, environmental influences, and neurological processes involved. Should society punish them? The determinists would say that punishment should not be based on retribution but rather on rehabilitation or deterrence because people do not have ultimate control over their actions. Compatibilists, however, maintain that accountability is compatible with determinism; what matters is that the individual acted in accordance with their character and motivations. This nuanced view aligns with the structure of many legal systems, which consider intent and circumstances while acknowledging external influences.

Beyond the courtroom, the question of free will has profound implications for personal identity and meaning. If our choices are predetermined, does this somehow deplete our sense of free will and self-determination? To some, the deterministic view brings comfort: a belief that life is some intricate tapestry, in which every thread interconnects to form part of a greater story. Others find the existential burden of determinism crushing, wishing they had the power of self-determination. Curiously, psychological investigations indicate that belief in free will is associated with increased motivation, better conduct, and better mental health. This leads to a curious paradox: even if free will is an illusion, believing in it may have real benefits.

Most objections to determinism rely on the inadequacy of science as it stands today. There are those who argue that human consciousness and decision-making involve layers of complexity that cannot be reduced to simple explanations. The interplay between biology, culture, and individual experience generates a dynamic system that resists reduction to simple categorization. On the other hand, emergent phenomena advocates argue that free will could be an emergent property of complex systems, much like life emerges from inanimate matter. This view bridges the gap between deterministic laws and the lived experience of choice, suggesting that free will might exist on some other explanatory level than that of fundamental physics.

Ethical and technological issues also feature in the debate. For example, artificial intelligence challenges more traditional notions of agency and autonomy. As machines become ever more capable of decision-making, questions arise over their responsibility and the ethical frameworks under which they operate. If we cannot define free will in humans, how can we attribute it to AI? Further, the ability to manipulate behavior and decision-making through neuroscience and genetic engineering raises questions about autonomy and consent. These are developments that force us to confront the boundaries of control and freedom in ways we never have before.

Despite its abstract nature, the discourse on free will and determinism influences how we navigate daily life. It shapes our attitudes toward accountability, empathy, and personal growth. Recognizing the constraints imposed by biology and environment fosters compassion and understanding, while affirming the reality of choice inspires self-improvement and resilience. Striking a balance between these perspectives enables a more nuanced and humane approach to the complexities of human behavior.

In the end, the importance lies not in resolution but in the exploration itself. In teasing out these ideas, we make finer and finer sense of what it means to be human. Whether free will be an illusion or a profound truth, to question itself is the most empowering way to meet our existence. And with this questioning of interplay between determinism and choice, we are faced with that intricate tapestry of factors that make life, which challenges us toward both humility and agency in view of uncertainty.

Published December 20th, 2024