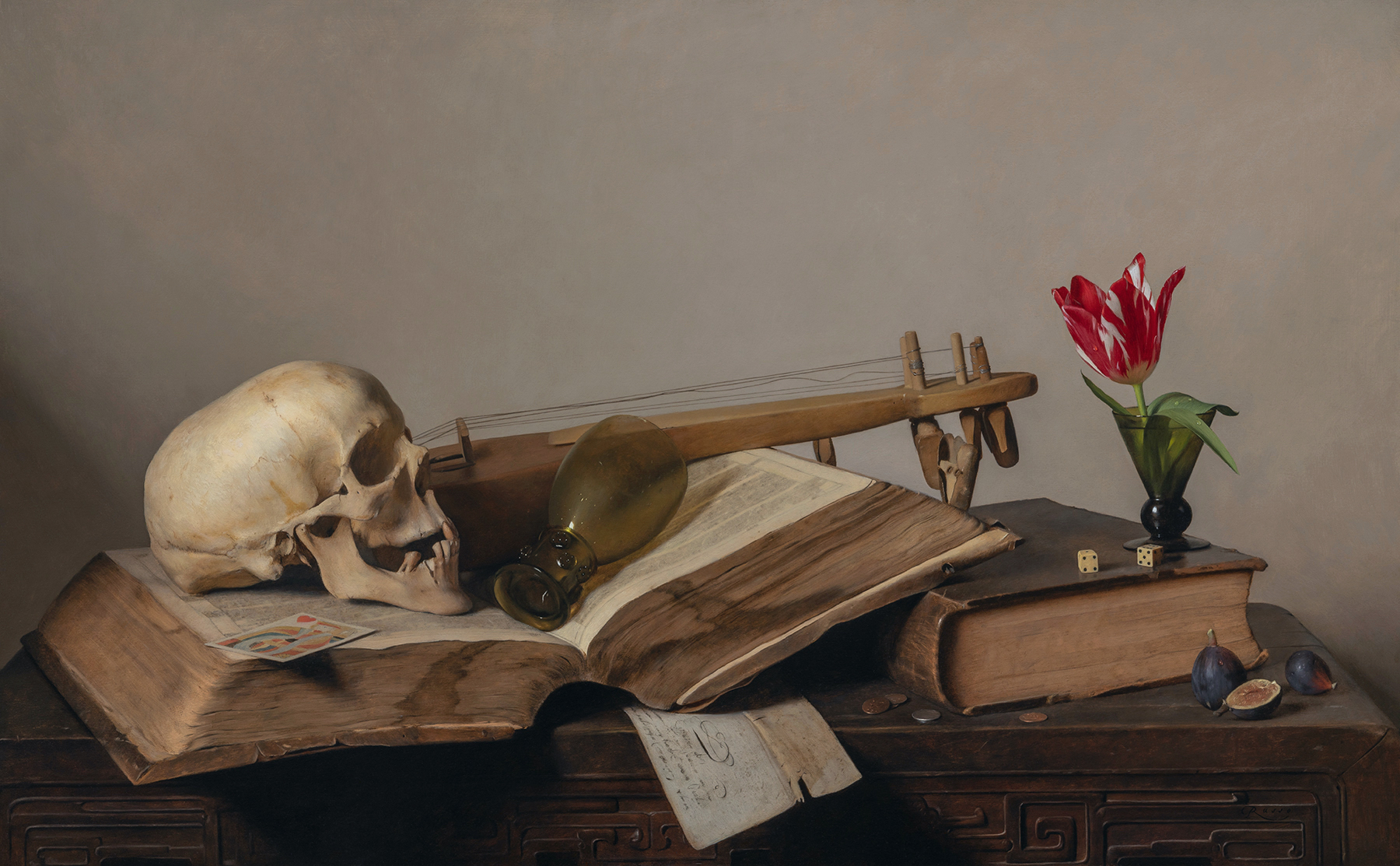

Memento Mori

The enduring question of life’s meaning has puzzled and inspired human thought for centuries, and among the many lenses through which to explore it, mortality remains one of the most profound. Death is far more than a biological endpoint; it is a defining feature of human existence that shapes how we understand life itself. By confronting the reality of our own finitude, we are compelled to ask what it means to live fully and meaningfully. Philosophical reflections on mortality—from existentialism and phenomenology to metaphysics and cultural traditions—shed light not only on the nature of existence but also on the creative ways individuals and societies construct meaning in the face of impermanence.

Mortality occupies a central place in existentialist philosophy, where thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus argue that awareness of death fundamentally transforms human experience. Sartre’s concept of “radical freedom” underscores how mortality strips away external justifications, leaving us responsible for defining our essence through conscious choices. This freedom, though daunting, offers a unique opportunity for authentic living. Each decision we make contributes to the creation of who we are, and the awareness of death lends urgency to this project. Camus, by contrast, focuses on the tension between humanity’s deep desire for meaning and the universe’s apparent indifference—a condition he calls the “absurd.” For Camus, however, this absurdity is not a reason for despair but an invitation to defiance. In The Myth of Sisyphus, he presents the figure of Sisyphus as an archetype for the human condition: despite knowing that life lacks inherent meaning, we can persist in creating purpose through our actions and attitudes. For both Sartre and Camus, mortality is not merely an end but a challenge—a call to live deliberately and boldly.

The existential struggle with mortality is also central to Søren Kierkegaard’s writings on anxiety and faith. Kierkegaard believed that the confrontation with death produces a profound sense of existential unease, but rather than viewing this anxiety as a problem to solve, he saw it as an opportunity for growth. Anxiety, for Kierkegaard, is a kind of existential wake-up call that forces us to grapple with the uncertainty of life. It is through this process that we are called to commit to our values and beliefs, even in the absence of guarantees. Mortality, then, becomes a catalyst for deeper authenticity, urging us to navigate the tension between despair and hope, between finitude and faith.

Martin Heidegger takes this exploration further, offering a phenomenological perspective on mortality in his concept of “being-towards-death.” For Heidegger, death is not just a distant event but a constant presence that defines the horizon of our existence. By acknowledging the inevitability of death, we are reminded of the urgency and preciousness of each moment. Heidegger argues that most people live in what he calls an “inauthentic” mode, avoiding the reality of death by immersing themselves in societal expectations and distractions. Yet, by facing our mortality, we can break free from these patterns and live with a deeper sense of purpose. Death, in this sense, is not merely a limitation but the condition that makes a meaningful life possible. Each moment, viewed through the lens of its transience, gains new significance.

Heidegger’s insights are complemented by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, who emphasizes the embodied nature of mortality. For Merleau-Ponty, death is not just an abstract concept or an endpoint but something intimately tied to the physical realities of being human. Our finite, vulnerable bodies shape how we perceive and experience the world, grounding the existential confrontation with mortality in the immediacy of lived experience. This perspective challenges purely abstract approaches to death, reminding us that our understanding of mortality is inseparable from the ways we live, move, and interact with others.

Beyond existentialism and phenomenology, metaphysical traditions offer additional ways of understanding mortality. Eastern philosophies, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, view death as part of a larger cyclical process known as samsara—the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. From this perspective, mortality is not an ultimate end but a transition, and present actions carry ethical weight in shaping future lives. In Western traditions, by contrast, metaphysical explorations often focus on the persistence of consciousness beyond death. René Descartes’ dualism, for example, posits a separation between the body and the soul, suggesting the possibility of an immortal essence. Contemporary theories, including those involving the multiverse or parallel realities, extend this inquiry, situating individual existence within expansive cosmic frameworks that challenge the finality of death.

Modern technological advancements, particularly those explored by transhumanism, add yet another layer to this discussion. By imagining a future in which human mortality might be significantly extended—or even eradicated—transhumanism raises provocative questions about the role of death in shaping meaning. If mortality is central to our understanding of life’s purpose, what happens when that condition is fundamentally altered? Would infinite existence diminish the urgency and significance of our choices? Or would new forms of meaning emerge in a world without death?

Psychology offers further insights into the relationship between mortality and meaning. Terror Management Theory (TMT), for instance, suggests that much of human behavior is driven by an unconscious fear of death. To cope with this fear, people adopt cultural worldviews—religious beliefs, social norms, or personal legacies—that provide a sense of symbolic immortality. Achievements, traditions, and shared values allow individuals to feel connected to something larger and more enduring than themselves. Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, meanwhile, focuses on the conscious pursuit of meaning, particularly in the face of suffering and death. Frankl argues that meaning can be found through creativity, relationships, and the way we respond to life’s challenges. His work emphasizes the resilience of the human spirit and its ability to find purpose even in the most difficult circumstances. Positive psychology builds on these ideas, highlighting practices like mindfulness, gratitude, and the cultivation of relationships as tools for living a meaningful, finite life.

Cultural responses to mortality also provide rich material for reflection. Across the world, societies have developed diverse rituals, narratives, and traditions to process the reality of death. Collectivist cultures often emphasize communal memory and shared practices, while individualist societies may focus on personal achievements and legacy-building. These cultural frameworks not only shape how people cope with loss but also influence how they construct meaning in their own lives. Whether through funerary rituals, storytelling, or artistic expression, these practices reflect humanity’s ongoing effort to confront the mystery of mortality.

Ethically, the awareness of death often heightens our sense of responsibility toward others. Recognizing our shared finitude can inspire greater empathy, encouraging us to prioritize meaningful relationships and acts of kindness. Altruism becomes a powerful source of purpose, as contributions to the well-being of others create a legacy that extends beyond individual existence. In contemporary times, this sense of responsibility has expanded to include environmental stewardship and global solidarity, linking individual actions to the broader continuity of life on Earth.

From ancient philosophy to modern psychology, the question of mortality has inspired countless perspectives, each offering unique insights into life’s meaning. Socrates believed that contemplating death was essential to the pursuit of wisdom, while Plato’s theory of Forms offered a metaphysical assurance of the soul’s immortality. In more recent analytic philosophy, figures like Derek Parfit have challenged traditional ideas of personal identity, suggesting that the self is not a fixed entity but a series of interconnected experiences. Such perspectives complicate how we think about death, raising profound questions about what it means for life to end.

Ultimately, the confrontation with mortality illuminates life’s depth and richness, urging us to create, reflect, and engage more fully. Death, rather than diminishing existence, reminds us of its fragility and potential. In embracing our finite condition, we find not only the limitations of life but also its extraordinary possibilities. The search for meaning in the face of mortality is not about discovering definitive answers but about committing to the ongoing process of interpretation and creation—a process that defines and enriches what it means to be human.

Published December 12th, 2024